East

The commercial center of my neighborhood is a hundred meters or so uphill walk from my house. There, locals and visitors sip on $12 glasses of wine, eat $15 burgers, and wander through boutique stores selling tchotchkes of all sorts from vintage black and white postcards to ceramic cats. I wonder how these establishments stay in business as, at times, it seems as if my sixteen-year-old daughter is their only patron, her room a shrine to unusual objects.

Some years back, the Target Corporation commandeered the local grocery store, an establishment where the manager, a man, sat in an elevated office watching both TV and his female employees. Locals protested the change, not wanting corporate influence to ruin our indie scene. Now Target acts as an anchor in the community. Their parking lot houses a local coffee shop and hugely popular fish taco truck. Right across from the lot is an apartment building where, more than twenty years ago, before I knew this neighborhood at all, I used to deliver food to a woman with AIDS. I volunteered with “Mama’s Kitchen” and she was a rare woman on my route. I try to imagine where her life journey might have taken her.

Food options tend toward Italian, Mexican, and bar food, but the punnily named “Curryosity” has also established itself as a neighborhood staple. Patrons sip cocktails in open air windows and the chicken vindaloo is hot enough to produce a sweat.

I love The Book Catapult, a local bookstore which hosts a monthly reading series and where I recently held my book launch. It was an emotional evening, filled with family and friends. The store was standing room only and the owners said they had a very good night. I puzzle over the economics. Rent there is $3000 a month and the store supports the owners who have two kids as well as three employees. Saturday afternoons find it bustling while on a Wednesday at that time it may be empty. I try to remember to buy a book a month, not all of them get read.

Sometimes, coming home from an evening reading or with croissants after an early morning stroll, I step around one or both members of a couple who sleep outdoors in the covered concrete well of a communal office workspace. Their affairs are neat, a bedroll and a backpack. Two of the all too many unhoused in my city. I live minutes away in an expensive home with a full refrigerator.

North

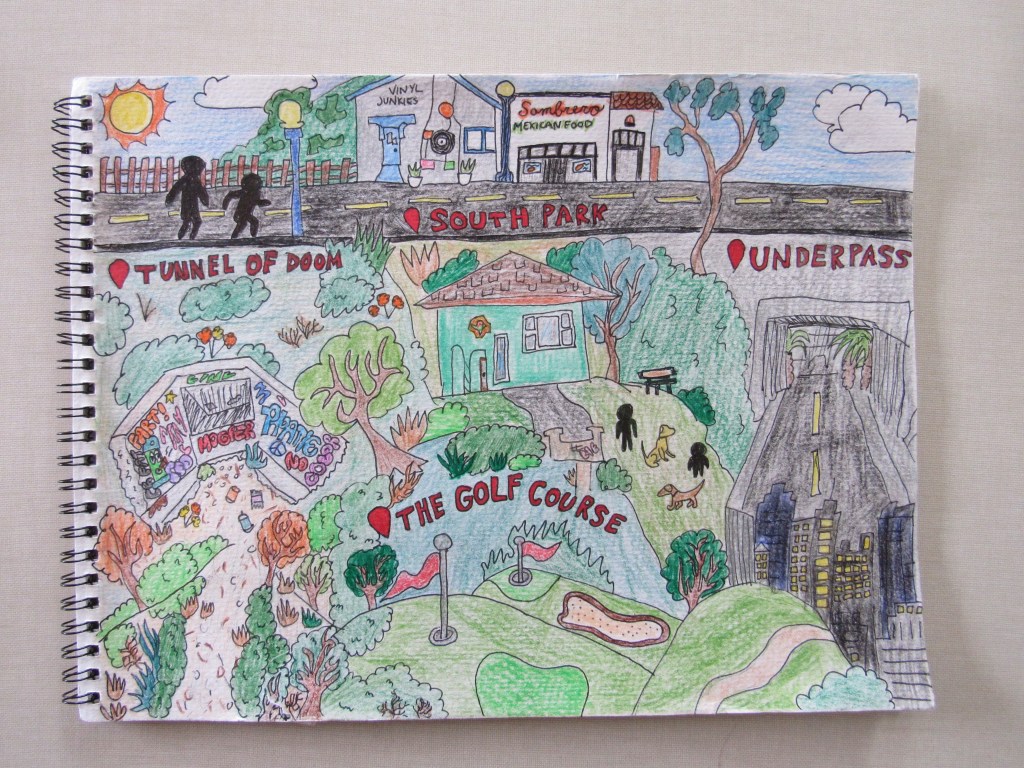

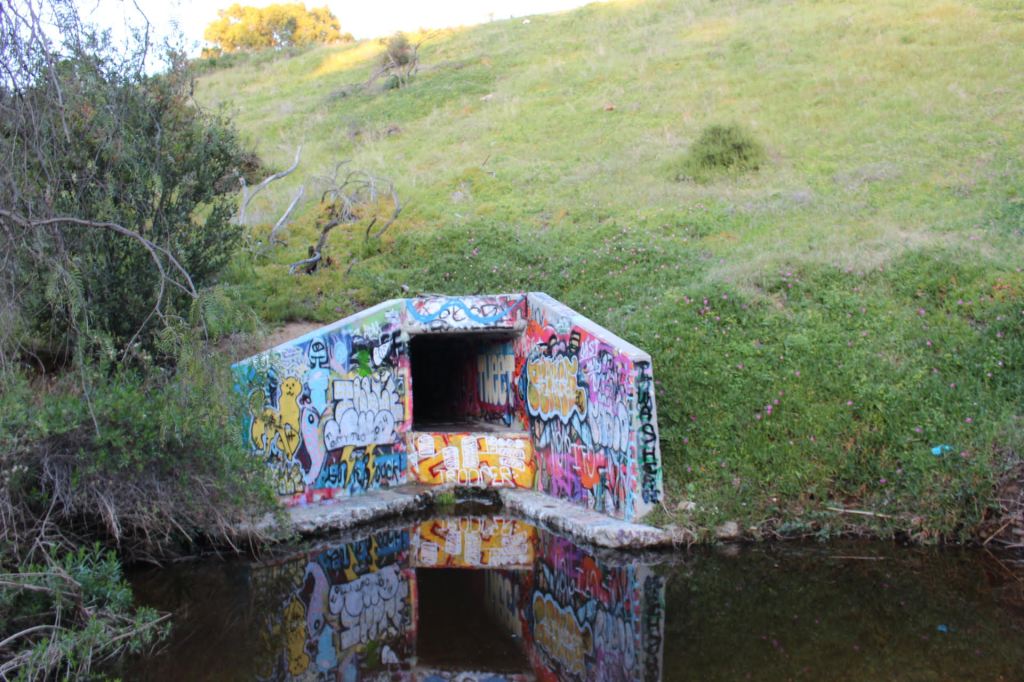

Walking north from my house, I pass over Switzer Canyon, a half-mile stretch of trees and shrubs which includes a large drainage pipe under 30th street, running 100 meters or so. When my kids were young, we called it “The Tunnel of Doom” and they’d run through it, their shouts echoing in the darkness. I’d follow hunched over, the tunnel too low for me to stand upright. On one side of the tunnel, the concrete entrance is covered in graffiti, colorful, yet at odds with the natural setting. On the other side, we discovered a rope swing, improbably affixed to a tree branch 20 meters high. The kids shrieked with delight as they cut through the air. The tree, like most of the others, is a eucalyptus, its distinctive smell and peeling bark, one of my first impressions when I moved to this city decades ago. Like much else here, eucalypti are not native to San Diego, the land of the Kumeyaay people. The trees were brought from Australia in the mid nineteenth century and are considered an invasive species and a fire risk, though now iconic in the state. The canyon also holds evidence of invasive humans. Beer and liquor bottles are not uncommon as well as other detritus. During the Covid lockdown, I’d walk the canyon with my trash picker, the task endless and, too often, depressing. Once my son and I encountered a dead raccoon above the canyon. It was dark and we crossed path with a lone woman, the animal at our feet. She was upset and I thought she might try to resuscitate the creature. I tried to tell her dead was dead, but there was too much grief those days.

West

In this country, heading west always means going toward the big, the open, the vast. About five miles due west of my house lies the biggest place on earth, the Pacific Ocean. But my neighborhood also holds intrigue in that direction. I slip around a concrete wall at the end of my cul-de-sac, and a short path through more eucalyptus trees leads me to a golf course. Some years ago, my children and I found magic there in the form of a lone coyote who’d sit on the fourth green and wait for dogs and their owners to show up at dusk after the golfers had cleared out. Then she’d play with the dogs, running in and out of the scrub as they lapped after her. We named her Sadie, and after she disappeared – rumor holding that the city removed her – my daughter and I wrote a story about her. Now I hear the coyotes at night and go to the course infrequently, wondering about its sustainability in a state with perpetual water issues.

On the other side of the golf course lies Pershing Drive, a one-mile formerly four-lane road which slashes through canyon as a link between my neighborhood and nearby downtown. The road used to maintain a 50 mph speed limit and several years ago, predictable tragedy struck. A cyclist was hit and killed by a motorist travelling at that speed. I cycle and my city is not a friendly one in that regard, the car being king, as with the rest of the state. Now, the city has decided close two lanes, reduce the speed limit, and make bike paths on Pershing. I hope against hope that the neighborhood will be more accepting of two-wheeled travelers. I bike on the trails alongside the road, my menaces rocks and erosion. One particular rock has been responsible for a broken clavicle, twice. Now, I avoid it, nature has won.

South

The mile or so south from my house is comprised of quiet streets with residential, single family homes, a mix of Spanish style with red tiled roofs and craftsmen style with large wood beams and porches. The houses vary in size but all are expensive in this market. Many owners have abandoned grass lawns, opting for drought tolerant plants instead. A few have citrus trees; after helping some elderly neighbors move a couch, I hold lifetime picking rights on their grapefruit.

The neighborhood ends at a freeway underpass where the homes have turned to apartments. Before the underpass is a busy intersection where cars can enter and exit the freeway. There’s a church which often has activity in its lot. Clothing drives and pop-up taco stands are common sights at night. The underpass itself is dirty and smells like urine, when I bike through I try not to breathe too deeply or look too carefully. Sadly, it is another spot where my fellow citizens sleep at night. I frequently see tents there in the morning as I cross it driving my kids to school.

On one morning, I saw a yellow school bus pull over in the dirt of the underpass. I wondered if there was a mechanical problem or if the driver had taken sick. A few minutes later on my return home, I saw that the driver, a slight man, was outside the bus, standing amid the trash, a horn in his hands. I slowed and lowered the window. He played, the jazz notes beautiful and haunting, a lone plastic bag swirling at his feet.

It’s been eighteen years, but the neighborhood retains its mysteries.

François Bereaud is a husband, dad, full time math professor, mentor in the San Diego Congolese refugee community, and mediocre hockey player. He is the author of the collection San Diego Stories published by Cowboy Jamboree Press. He has been widely published online and in print. The Counter Pharma-Terrorist & The Rebound Queen is his published chapbook. His work has earned Pushcart Best of the Net, and Best Small Fictions nominations. He serves as the fiction editor at The Twin Bill, and reads for Porcupine Literary. Links to his writing at francoisbereaud.com.

Chantal Lucas Bereaud is an 11th grade student at the San Diego School of Creative and Performing Arts, majoring in photography.